What’s the first tree you can remember? What did it look like? How did you interact with it? Mine was a giant sycamore that grew outside my house when I was eight. It had these sweeping, low-slung branches, which made it perfect for climbing.[1]

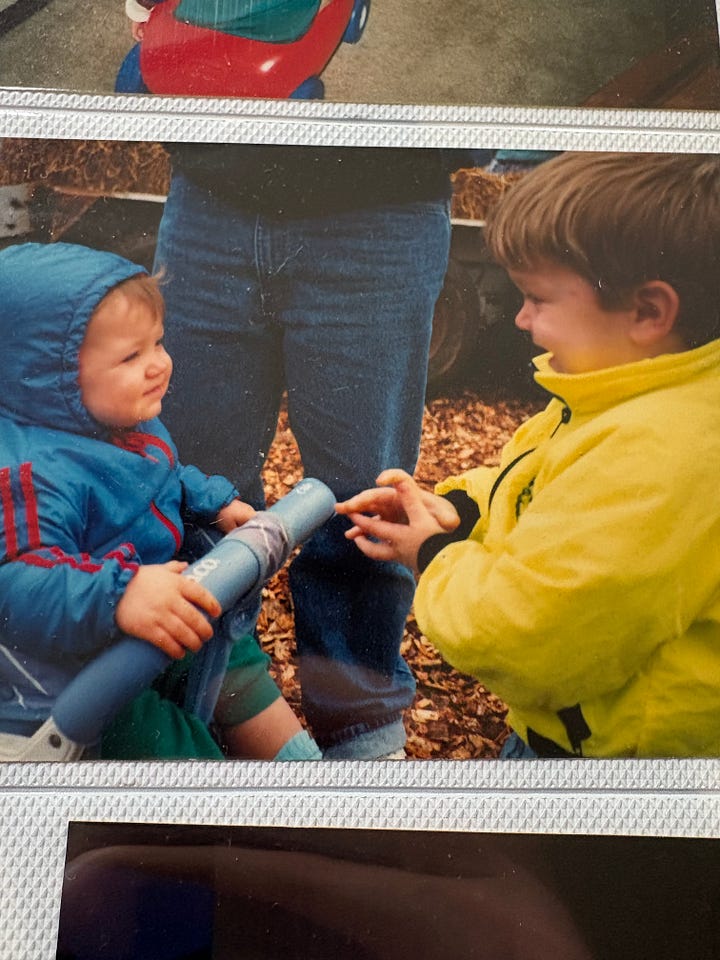

There were other trees, of course. So many wonderful trees. In the pictures below, you can see my highly pregnant mom planting one in honor of my most-anticipated – and ultimately disappointing – birth. Then, you have my brother and I playing in leaves (I am the smol babbin on the left). Leaves that came from – you guessed it – trees.[2]

The divine right of trees

This question though – what’s the first tree you can remember – is a good one. It makes nature a thing of memory, a thing that’s personal. It was a question posed by Anissa Camacho, a speaker at How to Live Well During Climate Change, a conference I attended at the University of Chicago Divinity School in early May.

Anissa is on the climate committee of The Puerto Rican Agenda of Chicago, and she was speaking about her environmental advocacy in the Humboldt Park neighborhood. One part of her work is working with neighbors on tree-planting, something that requires bridging what she called the “cultural-natural gap.”

For Chicagoans of all origins, it can be difficult to see trees as something personal – as something beyond a source of bird poop on their cars or leaves on their lawn. However, she’s found that through story-telling (an obvious passion of this Substack), it becomes easier to build those connections.

Many of the residents who grew up in Puerto Rico talk about the Yagrumo tree (a many-named beauty that also goes by la yagruma, yarumo, guarumo, or guarumbo, depending on the region). The tree can be a potent symbol in Puerto Rico, known for the silvery underside of its leaves that show when the trade winds blow – and hurricanes are coming. It was in talking about trees they remembered fondly from back home that the community was able to have a deeper conversation about the trees that surround them in Chicago now.

And before you dismiss all this tree talk as a romantic distraction, there are serious benefits to engaging on the urban canopy. For one, many residents are being pushed westward in the neighborhood by gentrification. Between gentrified and non-gentrified areas, there can be a temperature difference as high as four degrees, driven in large part by tree disparities. Anissa also noted that the Puerto Rican community has some of the highest rates of asthma, and planting more female trees can help with high pollen levels.[3]

Relationships are stories we tell each other

This theme of storytelling came up again and again throughout the conference, which is no surprise. Humans are relational creatures, and we had tens of thousands of years to perfect the art of storytelling before we started writing things down – and well before the advent of dry climate statistics that have apparently failed to win people over.

Another speaker was Naomi Davis, the founder of Blacks in Green. Her group has been building a “sustainable square mile” in West Woodlawn since 2007, piloting a community vision that brings neighbors together to invest in each other and prepare for climate change.

Beyond her group’s incredible work in horticulture, clean energy, and housing, one of their annual activities is a community performance. As Naomi said, it’s telling our stories that help us to fall in love with a place, the thing it takes to “sur-thrive” instead of just survive.

As the planet warms, this storytelling will be an essential part of how we navigate what’s happening in the world and how we’re living through it. So, what would your nature autobiography say? What do you know about the planet and when did you learn it? What do you still want to learn? What do you love about your neighborhood? How was it impacted by the last storm? In these answers, I think you’ll find hints about where your journey might take you next.

Good relationships = good results

Despite our many attempts at separation, our relationship with the planet is the core of who we are. In the second panel at the conference, I heard from Dr. Marc Berman, a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, who has studied just how vital nature is to human functioning. From bird sounds to the way the light moves through a tree canopy, the human brain was evolved specifically for nature.

When we’re in nature, our nervous systems are calmed almost effortlessly. As Berman has shown in his studies, we don’t even have to like it. He sent participants into nature in both summer (when presumably they liked being outside) and winter. Even the winter participants – who complained about how cold it was – ended up faring better on cognitive tests after their time outside.

This has sociological implications too. Being around nature increases cognitive resources and improves self-control. In another study, Berman found that communities averaging just one visit to a park per month were correlated with violence reductions of 14%. Poverty, of course, is a central driver of violence, but strangely, replacing the effect of that single park visit would require a reduction in poverty of 41%. As Berman noted at the conference, we should clearly be doing everything we can to reduce poverty. However, his studies are also a wakeup call that “nature isn’t an amenity, it’s a necessity.”

When relationships go bad

So far, these examples have made it fairly obvious that we thrive when nature is healthy. However, relationships are also a two-way street. We shouldn’t think only of what get from our relationship with nature, but also what is owed.

A few weeks back, this idea was brought home for me on the Modern Love podcast. They interviewed Terry Real, a relationship therapist and expert in toxic masculinity / male vulnerability. (Which, by the way, is no mere sociological abstraction for Terry. He grew up with an abusive father whose own father had abused him – creating a cycle of pain that needed to be healed.)

What we see in toxic masculinity is a paradigm of dominance, a paradigm that causes pain for everyone involved, both men and women alike. Healing that kind of paradigm, meanwhile, requires relationality. It requires moving from an attitude of gratification and “what do you got for me” to an attitude of connection and “what do you need from me?”

Dominance, meanwhile, is the very same structure we see in our relationship with nature. With a brand of capitalism that’s purely extractive, we take beyond the breaking point, seeking gratification in place of sustainability. But here’s the thing – good relationships require sustainability. They require an understanding that there’s some future beyond the present moment, some greater good we’re sacrificing for.

It's not to say this is easy. As Terry notes in the podcast, being a good father and husband can sometimes be a real pain. It requires effort, patience, and self-control. However, there’s so much joy on the other side. That, ultimately, is what good relationships are for. They’re regenerative, giving back and creating something worth more than the sum of their parts.

To that end, when asked why men should listen to him, Terry says, “because it’s in your best interest.” It may take work to have a good relationship with nature – after all, convenience is addictive – but it’s not like unfettered capitalism is making us all that happy, anyway. By all measures, people are lonely, anxious, and exhausted, with rugged individualism keeping us isolated and shopping. Why not try something new? Why not try a capitalism that’s regenerative?

Hope is on the other side

Last month, I got to participate in Chicago River Day, a bonanza of volunteering across 92 different sites in the Chicago watershed. And this year, the 33rd year of River Day, saw nearly 3,000 volunteers come out to improve the health of Chicago’s wetland ecosystem. I, along with a bunch of my stalwart climate friends from Citizens’ Climate, wound up on the south side of Chicago at Indian Ridge Marsh – so far south, in fact, that we were only a few-minutes’ drive from Indiana.

Our mission? To plant as many wetland plants as we could, plants that will continue to improve the health of the marsh. In the end, covered in muck, we’d managed to plant 2,500 of the little guys. It was in the site itself, however, that I felt like I could see the long arc of Chicago’s history – both how our past led us here and where we can get to next.

Indian Ridge Marsh Park is only about 143 acres today, but it was historically part of a wetlands system that spanned 20,000 acres. The ridge, meanwhile, is so named because it was a bit of high ground in the wet prairie that served as a way-station for native populations – populations that were forced out by white settlers. Then, of course, we had a century and a half of industrialization, when the area became the site of the Acme Steel Coke Plant before it was abandoned and made into a superfund pollution site. Working on the marsh, you can even see the old smokestacks!

Thankfully, that wasn’t the end of the story. Through the diligent work of park rangers and community members – and the occasional mud-covered Carbon Fables writer – the marsh is making a bold comeback. Herons wander in the water, and our little plantings have dug their roots into the mud where they’ll grow big and strong. In the long story of our relationship with the marsh, it seems we’re finally entering a healing phase.

The wind rises

Unfortunately, it’s impossible to write this month’s Substack without recognizing that our relationship with nature is filled with ebbs and flows. And currently, we’re definitely on the precipice of a mighty ebb. When the House passed their “big, beautiful bill” for spending, they repealed nearly all of the Inflation Reduction Act’s climate measures – even as those programs have sent dollars 3:1 to Republican districts and created thousands of factory jobs.

The results of this – though many hope it will be softened in the Senate version – are going to have an undeniable climate impact. As Bill McKibben wrote in his Substack, The Crucial Years, Princeton compiled some astonishing stats on what IRA repeal could mean for the US:

0.5 billion more metric tons of emissions per year by 2030

Increased US household energy costs by $100-160 per household per year by 2030 – an increase in aggregate of $25B per year

Reduced investment in the US by $1 trillion from 2025-2035.

Put at risk $522B in pending investments in clean energy manufacturing

Reduced EV sales by roughly 40% by 2030

Increased average retail electricity rates and monthly household electricity bills by about 9% by 2030

That’s pretty daunting, but now is not the time to give up. Mankind has faced challenges before – even self-inflicted ones – and we’ve risen to meet them. In the movie The Wind Rises, Hayao Miyazaki quotes the French poet Paul Valéry, “The wind is rising!... We must try to live!” Valéry, of course, was talking about the rise of Naziism in Europe, but it’s also the perfect metaphor for our weather-pattern-defying times. We must try to live - and we must try to change.

While running in the opposite direction from climate progress will almost certainly bring more pain, it’s pain I hope we’ll learn and grow from. In the long arc of our relationship with nature, I even hope we’ll find a turning point. Like the marsh, we’re creatures in need of renewal, of finding a new relational way to live. After all, you don’t get through an apocalypse in a bunker. You get through it with your friends. Let’s go make nature one of them.

*Art by Charles Logasa, Men at a Table, 1932, Courtesy National Gallery of Art

**Email header art by Karl Nilsson (sigvardnilsson on instagram), includes portions of Beck's Castle Ruins by László Mednyánszky Denbigh Castle, W he ales by Edward Dayes & Paysage de la Grand Chartreuse attributed to Jean Lubin Vauzelle

[1] Presumably, that’s why sycamores show up in the Bible – my boy Zacchaeus shmurping his way up one to get a look at Jesus.

[2] I really thought I had a picture of my sycamore, but I guess I don’t? Thankfully, it’s still there – I drive by sometimes to check on it, much to the current home owner’s chagrin.

[3] As you may have heard, pollen levels in cities are often driven by “botanical sexism” and the obsession with only planting male trees in the mid-1900s.