Blowing smoke

Air quality and grass roots climate action

The story of climate change is the story of air pollution. Maybe this feels obvious when you’re stuck in traffic behind a modified Honda Civic that’s belching smoke into your cabin filter. But most of the time — for me, anyway — when we talk about CO2 levels of 420 parts per million, “the air” can seem a bit abstract.

But you don’t just magically get massive amounts of CO2 into the sky. It’s point source pollution gone global, the combination of billions of smokestacks, tailpipes, and fires. In fact, starting in the 1800s, with the Industrial Revolution, Britain burned so much coal that the Peppered Moth mutated to hide against tree trunks covered in soot.

By those standards, the air now seems pretty clean — at least visibly. Starting in the ‘50s with the first edition of the Clean Air Act, we’ve come to regulate nearly 200 air pollutants, including things like lead that used to be regularly added to gasoline. And yet, the UN has reported that air pollution is still causing nine million premature deaths per year with climate change only making matters worse — as rising temperatures feul wildfire smoke and higher ground-level ozone.

Of course, the Industrial Revolution was an essential step on the path to modernity. As Ember Energy has written, the high energy density of fossil fuels allowed us to get off of candles and whale blubber and into electric lighting. And as Hannah Ritchie recently wrote in her most-excellent newsletter, while the modern age is a tale of “environmental pressure,” it’s also a story of rapidly falling poverty, higher living standards, and growing freedom.

This then, is our opportunity. We are poised at the threshold of what Ember calls the “Age of Electricity,” our chance to use better, cleaner technologies without sacrificing modernity. Any change, however, is politically fraught — who wins and who loses as we modernize is a political question that bears answering.

But I’m beginning to wonder if air quality isn’t a way to bring people together on the changes we still need to make. While only 45% of Americans say human activity causes climate change, a much higher 60% of those same Americans want the government to do more on air quality. Every one of us, regardless of politics, breathes 30 pounds of air each day across 25,000 breaths. Maybe that can unite us.

Testing…testing…. (Is this thing on?)

I bring you this topic today because of a very nifty program I recently had the pleasure of participating in. For long-term readers of the Sub, you may recall that my rainbow flag church in Chicago has been working with Faith in Place to lower our building’s footprint. Earlier this year, that work included getting $11k from our utility to update the church’s lightbulbs — cutting our energy use by 15% and taking $1,000 off our annual bills. And we’re only in the early innings, with energy consultants currently helping us assess our HVAC.

This month, however, Faith in Place is doing something really special on air quality. Using households in their network of churches, they’re conducting a home air quality study to track levels of indoor pollutants driven by fossil-fuel-powered appliances. The most important one is the stove — which I covered in my third ever post, Benzene Maxxing — though gas furnaces also impact things.

Even better, Faith in Place isn’t simply testing the air and running off into the night. They’re leaving behind beautiful little induction cooktops so participants in the study can improve their air quality right away! My church’s portion of the study is being conducted by our legendary Green Team leader, Xander. But I got to witness one testing session at a friend’s house —a sort of environmental ride along, if you will — but I’m here to tell you all about it.

The process

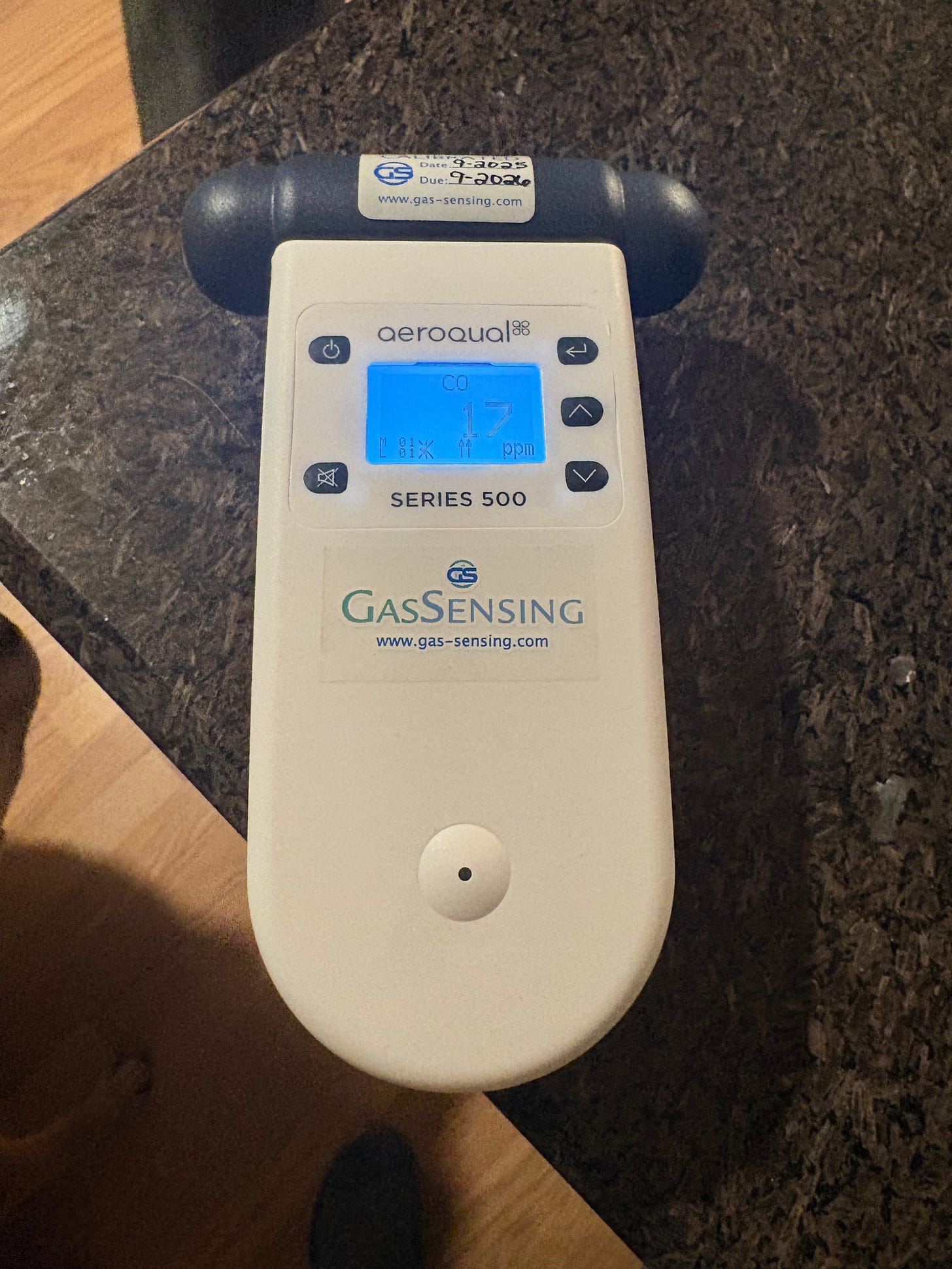

If you’re going to test the air, you need an…air…testing…device. Enter the Aeroqual 500. It’s a portable unit capable of detecting 16 different pollutants. You just have to switch out the testing heads and recalibrate between pollutants — which wound up being the majority of the time it took us to test.

In theory, natural gas is mostly methane (CH4). If it burns “completely” it should only produce water vapor and CO2. While most of what your appliances emit is CO2 — which is the climate issue — there are lot of other nasties and byproducts that can harm your health. These can come from incomplete combustion (i.e. not enough oxygen present) or from elements that form under the high heat of flames. In the study, we’re focused on two toxins in particular:

Carbon monoxide (CO) – This is one we’re all familiar with (and often have sensors for). It forms from incomplete combustion. It is colorless and odorless, but is dangerous in high concentrations. While typical cooking won’t lead to levels that kill you, they decrease your air quality and can create chronic exposures.

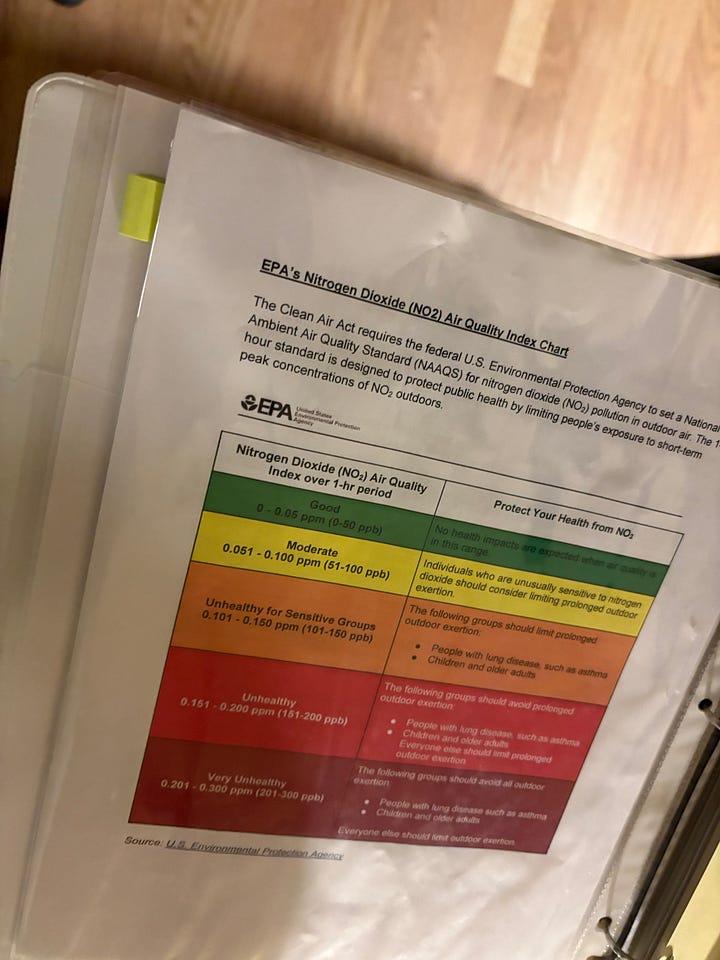

Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) – Because gas stoves burn at high temperatures, they can cause atmospheric oxygen and nitrogen (the two most common air elements) to combine. This does not come from the natural gas itself but from the flame’s interaction with the air.

Faith in Place provided some helpful leave behind flyers on the health risks. Air quality issues can lead to increased risk of asthma, impaired neural development for children, and increased cardiovascular risks. There are currently no federal standards for home air quality, though international and domestic outdoor standards point to limiting long-term exposure at high levels.

By the way — while we weren’t testing for benzene, that carcinogenic nightmare is also leaking into your house. Benzene is a ring-shape hydrocarbon, C6H6. While natural gas naturally contains some benzene, it also forms from incomplete combustion when the leftovers of your methane’s CH4 reorder themselves. However, because of the naturally occurring benzene, a slow leak of the stuff occurs even when your appliances aren’t on. Yippee!

My ride along

With our friend Austin graciously opening his home for testing, we set about making an ideal testing environment. By that, of course, I mean we petted his dogs and gave them treats. This was done so that the dogs would realize air quality is the threat, not us!

Next, we tested for carbon monoxide around the apartment to get a baseline. Since the stove wasn’t used at all during the work day, this was driven by the furnace. We had a reading of 21 ppm (parts per million) right next to a furnace and 18 ppm from two of the furnace vents. While CO detectors generally won’t go off until 70 ppm or higher — viewed as “life safety devices” — the World Health Organization’s 24-hour guideline for CO is just 4 ppm.

Finally, we turned on two stove burners and set the oven to 350 degrees. Testing at 15- and 30-minutes, the carbon monoxide in the kitchen climbed to 26 ppm and then 31 ppm. Testing for NO2, we started with a baseline of 0.019 ppm, which rose to 0.079 ppm at the 15-minute mark and 0.251 ppm after 30 minutes. As you can see in the grid below, this put us solidly in the “danger zone” for outdoor quality, like when wildfire smoke makes it dangerous to exercise.

The limitations of testing

As I noted at the top of this piece, I’m always a little hopeful that something else — like air quality — will motivate people to take climate action. Whether you get a heat pump for the climate, the efficiency gains, or the air quality, I will thank you regardless. However, it’s also clear that even using air quality as a motivation doesn’t take away the structural barriers to electrification. As we conducted the interview portion of the study, a few things were clear:

Cost matters – While the poor air quality of fossil fuel appliances is motivating, it doesn’t change the fact that getting an electric oven (as I documented at my house here) can potentially require 240V rewiring and the purchase of a new appliance. (Would that we were in Europe, where everything automatically runs on 240V…).

Thankfully, both recent and past policies seem to understand this. The now repealed Inflation Reduction Act (RIP) included subsidies for both wiring and electric ovens. In Illinois, the recently passed Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability Act (CRGA) increased the amount utilities have to spend helping customers become more energy efficient – though this is focused only on low-income households.

Culture matters – While gas stoves are in the minority in this country (only around 40M households), that doesn’t change the fact that people who like them care about them A LOT. (Never mind that a lot of this preference was driven by pro-gas marketing in the 1950s). This leaves homeowners in a potential bind. Do you change the appliance ASAP or when you’re in your forever home where prospective buyers’ opinions no longer matter? If you are a buyer, are you duly excited when you see an electric oven (as you well should be)?

Meanwhile, don’t forget that outright bans tend to be a political disaster. Nationally, “hands off my stove” has become a rallying cry on the right. But even in Chicago, you may recall that attempts to pass the Clean and Affordable Business ordinance (CABO) led to an open revolt on the City Council. Besides, I think the Abundance agenda has made it clear that more layers of byzantine rules is not the road to having adequate and affordable housing. The key then remains changing the culture. If no one is demanding gas appliances, it won’t matter if we ban them or not.

Infrastructure matters

We’ve covered extensively in this Substack the benefits of electrification from an economic standpoint. Electric appliances tend to be far more efficient than their gas counterparts, which can help save money long-term. However, while electricity is still generally affordable compared to gas, we’re seeing enormous cost pressures on the electricity side.

After a summer where the average electric bill in Chicago jumped 180% — due to data center demand and policies at our grid operator, PJM — PJM’s December capacity auction hit another fresh record of $16.4B. This will get passed on to utility customers, which will in turn hurt the relative cost of electrifying. (Though, not to be outdone, People’s Gas, our natural gas utility, is also working on passing on huge infrastructure costs to consumers).

We desperately need permitting reform to improve our grid and speed up the buildout of low-cost renewable energy resources. CRGA helps to do some of this in Illinois, but we need national action too. The good news is, some proposals in Congress seem to finally be gathering steam. Call your legislators to tell them to do something!

And that’s it! Hopefully this was informative and not overly spooky. I also hope it doesn’t make you feel stuck. As we’ve always said here at the Carbon Fables, electrification is a marathon and not a sprint. Thankfully, before spending thousands on rewiring, you can get those little induction cooktops for $100 or less. That means better air quality could be within reach without major upgrades. Either way, next time you’re cooking, take a deep breath of whatever you’re roasting up — and then immediately go open a window.

With love,

JH

*Art by Joseph Pennell, The Coal Mine, 1916, courtesy National Gallery of Art

**Email header art by Karl Nilsson (sigvardnilsson on instagram), includes portions of Beck’s Castle Ruins by László Mednyánszky Denbigh Castle, W he ales by Edward Dayes & Paysage de la Grand Chartreuse attributed to Jean Lubin Vauzelle